The iconic Piscator sculpture by acclaimed Post War artist Eduardo Paolozzi no longer holds court outside London's Euston Station. It removal seems something of a slight to a true British Pop Art pioneer.

For decades, commuters spilling out of London’s bustling Euston Station were greeted by a strange but familiar guardian: a vast abstracted head, gleaming, at least in its early years, like a futurist relic from another age. The sculpture Piscator, created by the celebrated Post-War artist Eduardo Paolozzi, once stood proudly on the station forecourt, an unlikely yet beloved fixture of the capital’s public art landscape. Today, however, Euston’s “Head” is gone, removed during redevelopment works and leaving behind a strangely empty space where modernism once met the everyday. Its disappearance feels, to many, like a quiet slight against a genuine British Pop-Art pioneer.

A Sculpture Lost to Neglect

That the removal of Piscator ultimately happened is, in hindsight, both predictable and dispiriting. For years the sculpture cut an increasingly forlorn figure, its once-bold surface dulled by grime, its aluminium finish destabilised by rust and weathering. The real mystery was not the damage itself but why it was allowed to decay so completely.

Commissioned by British Rail in 1980, the giant cast-iron work was intended as a major piece of public art—an emblem of 20th-century abstraction and a nod to the German theatre director after whom it was named. Its distinctive silver bumps and hollows were said to evoke both body and head when viewed from above, hence its affectionate nickname: “Euston’s Head.” Though not always universally adored—some dismissed it as a lumpen slab lacking the organic warmth of a Henry Moore—it quickly became part of the visual vocabulary of the station, a piece of sculpture encountered not in a gallery but in the daily churn of London life.

By the 2010s, however, Piscator was showing advanced signs of deterioration. The oddest part of the story is that, for years, nobody seemed willing to admit ownership of it. As rail services moved through waves of restructuring and privatisation, responsibility for the sculpture became lost in bureaucratic fog. A major public artwork by one of Britain’s most important 20th-century artists—worth hundreds of thousands—was left in limbo.

Eventually, the sculpture was declared the property of Arts Council England, and as part of the latest redevelopment works at Euston, the decision was made to remove it altogether. With the HS2 Euston redevelopment now on hold, the station sits both physically and symbolically headless.

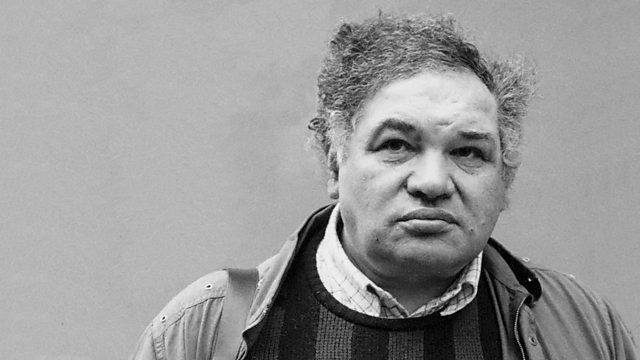

Eduardo Paolozzi photographed in 1990 for the BBc's Desert Island Discs.

A Slight Against a Pop-Art Trailblazer

The quiet disappearance of Piscator feels especially unfortunate given the stature of the man who created it. Born in Edinburgh in 1924 to Italian immigrant parents, Paolozzi’s early life was marked by real trauma. When Italy entered the war against the United Kingdom in 1940, he was interned for three months at Saughton Prison. Even more tragically, his father, grandfather and uncle—also detained—were among the 446 Italians who died when the Arandora Star sinking was torpedoed en route to Canada.

Despite this devastating loss, Paolozzi pursued his artistic education with determination, first at the Edinburgh College of Art in 1943 and later at the Slade School of Fine Art from 1944 to 1947. It was during these formative years that he began assembling the collages that would help define the Pop-Art movement. Among them was the landmark 1947 composition I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything, a pivotal piece that not only captured the era’s fascination with American imagery but also became the first artwork to incorporate the word “pop.”

I Was A Rich Man's Plaything (1947).

As a central member of the Independent Group, Paolozzi helped usher mass culture into the realm of high-art discussion. The group’s now-legendary 1952 “Bunk!” presentation, which included the Plaything collage, is widely considered the public birth of Pop-Art in Britain. This celebration of advertising, consumerism and visual noise would feed directly into the cultural explosion of the 1960s—an era when music, fashion and graphic design absorbed bold, brash Americanised imagery with gusto.

Naturally, anyone invested in 60s style, including us at Madcap England, recognises the deep links between Pop-Art and the Mod aesthetic. Pete Townshend once said of The Who, “We stand for pop art clothes… We live pop art.” In that sense, the vanishing of a major public artwork by one of the movement’s key architects isn’t just a concern for art historians—it’s a cultural loss for retro fashion enthusiasts everywhere.

Paolozzi’s Other London Landmarks

There is at least some comfort in knowing that Paolozzi’s work still punctuates the capital. Since 1990, the striking bronze Head of Invention (1989) has been a prominent feature of the Design Museum, while perhaps his most famous sculpture, Newton (After Blake) (1995), sits proudly outside the British Library. And for those who prefer Paolozzi at his most colourful, the vibrant mosaics at Tottenham Court Road Station—nearly lost during the Crossrail expansion—remain a joyful, sprawling celebration of his aesthetic.

These works remind us just how embedded Paolozzi is in London’s artistic fabric. They also make the absence of Piscator feel all the more glaring. Sculptures like these aren’t simply decorative—they are anchors of cultural memory, markers of creative ambition in places where millions pass each year.

A section of Paolozzi's Mosiac at Tottenham Court Road Station.

A section of Paolozzi's Mosiac at Tottenham Court Road Station.

Forty-Five Years On: Time to Restore the Head?

This year marks 45 years since Piscator was first unveiled outside Euston Station. Half a century is a significant milestone for any public artwork, and it seems almost unthinkable that the sculpture might spend its fiftieth anniversary hidden away rather than restored and reinstalled.

Euston has been without its Head for far too long. Whatever final form the station’s redevelopment takes, the case for returning this strange, striking and historically important work to its rightful public place grows stronger with each passing year. Paolozzi’s legacy deserves visibility, and London deserves back this quietly iconic piece of its cultural landscape.