A Brief Cultural History of the Mod Target: From Heraldry to Pop-Art to Subculture Icon

A ubiquitous symbol attaching itself to all things Mod or, depending on who you ask, all things not Mod, the target logo has undeniably become a cultural icon in its own right. Whether emblazoned across parkas, badges, album sleeves or scooter panels, this simple concentric circle has come to represent far more than the sum of its shapes. It is at once patriotic, ironic, artistic, stylish, commercialised, rebellious, and depending on your flavour of Mod, slightly contentious.

Yet for a symbol so strongly associated with 1960s youth culture, the target’s story begins centuries earlier.

Medieval Origins and Military Reinvention

Naturally, the roundel was no 1960s invention. Variations of concentric circles appear throughout European heraldry as far back as the 12th century, adorning shields, banners, and insignia. Simple, bold, and unmistakable from a distance, the design functioned as a medieval brand logo: clear, communicative and immediately identifiable on the battlefield.

Fast-forward seven hundred years to the skies of the First World War, and the target re-emerged in a startlingly modern guise. The French military aviation authority, predecessor of today’s Armée de l'Air et de l'Espace, adopted a tricolour roundel painted on aircraft fuselages and wings. Its purpose was pragmatic rather than artistic: to prevent friendly fire by allowing ground troops to recognise French planes at a glance.

The British soon followed suit. After experimenting with several marking systems, the newly established Royal Air Force opted for a target-like insignia of its own. Maintaining the French circular structure but reversing the colours, the RAF roundel became its defining visual mark, a symbol still used today.

This marriage of form, clarity, and national identity would later make the roundel irresistible to artists seeking imagery at once familiar and abstract.

Pop-Art Discovers the Roundel

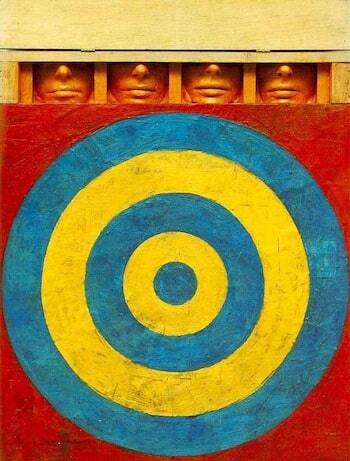

It wasn’t until the late 1950s that the roundel made its leap from military marking to artistic motif. Its transition began with American artist Jasper Johns, whose early career was built upon transforming everyday icons; flags, maps, numbers into textured, ambiguous works. After destroying his earlier pieces in 1954, Johns embarked on a series of paintings that reimagined common symbols through expressive brushwork and thick encaustic layering.

One of the most influential was "Target with Four Faces" (1955), a work that fused the geometric precision of the bullseye with rough, tactile strokes and four plaster-cast female faces partially concealed behind wooden doors. This merging of the universal and the unsettling helped elevate the ordinary roundel into a charged cultural object.

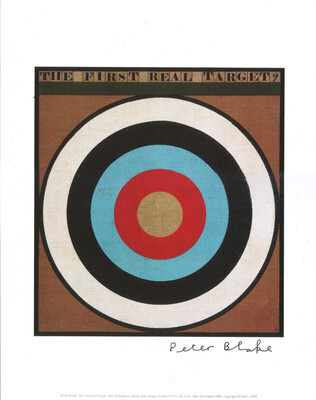

Across the Atlantic, British Pop-Art figurehead Peter Blake was paying close attention. In 1961, Blake bought a ready-made Slazenger archery target, repainted it with acrylics to heighten its immediacy, and titled the work "The First Real Target". Some saw the piece as a cheeky jab at Johns, suggesting Blake had created not just an artwork of a target but an artwork that was a target, an escalation of Pop-Art’s fascination with blurring object and image.

Blake later clarified that his intention was to challenge artists who used target-like motifs without acknowledging their real-world function. By presenting a literal, recognisable target repurposed as art, he exposed the comfortable contradictions within abstract painting.

Whatever the interpretation, the roundel had officially become a Pop-Art staple.

From Galleries to Guitars: The Who and the Rise of the Mod Roundel

The leap from Pop-Art to youth fashion came quickly, and loudly. In the early 1960s, the emerging British beat scene embraced bold graphic motifs, and few bands were bolder than The Who. Under the guidance of their first manager, the influential Mod figure Peter Meaden, The Who’s image initially reflected sharp Mod style. But when the band began adopting Pop-Art visuals; including arrows, Union Jacks, and of course the target. Meaden was unimpressed.

To him, Pop-Art had nothing to do with Mod philosophy, and he accused the band of selling out. Strikingly, the band partially agreed. Speaking to Melody Maker in June 1965, Pete Townshend remarked, “We think the Mod thing is dying,” praising Pop-Art instead and even calling their single “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere” the first true Pop-Art record.

The roundel then became firmly embedded in The Who’s evolving iconography; most famously on a white turtleneck worn by their legendary drummer Keith Moon. With the image now tied to swinging London, art-school irreverence, and high-volume rock, the symbol took on new life.

Reinvention: The Mod Revival and the Roundel’s Second Birth

Although Meaden may have been correct in claiming the roundel had little direct connection to original 1960s Mod culture, things changed dramatically during the Mod revival of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Bolstered by the success of The Who’s film adaptation of "Quadrophenia" and bands like The Jam, the new wave of young Mods embraced the target with unrestrained enthusiasm.

Whether painted on scooters, stitched onto jackets, or incorporated into posters and fanzines, the roundel was suddenly everywhere. The Pop-Art energy of the 60s collided with the sharp style and attitude of the Mod revival, cementing the symbol as the subculture’s unofficial international logo.

By this point, the debate over whether it was “authentically Mod” became largely irrelevant. It looked Mod. It felt Mod. And it worked.

A Perfect Symbol—Mod or Not

So is the Mod target the definitive symbol of Mod culture, or a signifier that purists should avoid? Honestly, who cares?

What matters is that the design is timeless; clean, bold, direct, geometric and undeniably cool. It adapts effortlessly to alternative colour schemes, scales beautifully from small badges to billboard-sized murals, and suits any medium from textiles to digital graphics. Its visual clarity gives it broad appeal, allowing it to transcend subcultures while still maintaining a fiercely loyal connection to them.

Perhaps that’s why both Mods and non-Mods have claimed it so passionately. The target is democratic: simple enough to be universal, stylish enough to feel exclusive, and flexible enough to carry whatever meaning its wearer wants it to carry.

In short, the Mods, and everyone else, are lucky to have it.